I came across an interesting video clip on Instagram that led me to poke around a bit. What I found was pretty interesting. I am intentionally avoiding to come to a conclusion, but I do tend to lean towards a particular bent…. but I will leave it up to you to decide for yourself.

THE WALUM OLUM

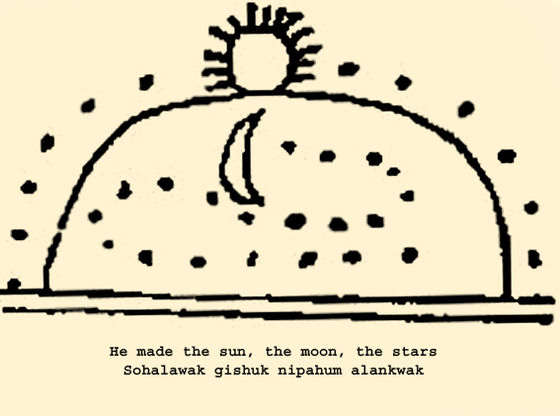

The Walam Olum, also known as the Red Record, is a controversial text that claims to be a historical and mythological account of the Lenape (Delaware) Native American tribe. It was first published in the 1830s by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, who said he translated it from pictographs inscribed on wooden tablets given to him by a mysterious source.

For decades, some scholars have treated it as a genuine Native American document, despite its murky origins and questionable linguistic accuracy. However, by the late 20th century, deeper investigations, especially by researcher David Oestreicher, revealed substantial evidence that Rafinesque likely fabricated the entire text. Oestreicher examined Rafinesque’s papers and consulted with Lenape elders, concluding that the Walam Olum was not an authentic tribal record but rather a constructed narrative that reflected 19th-century ideas and biases.

While the Walam Olum may have historical significance as a cultural artifact of its time, it is no longer considered a legitimate or authentic record of Lenape tradition by modern scholars and Native communities.

IS THIS A “SCIENCE-BASED OBJECTION”?

While the majority of scholars today consider the Walam Olum to be a fabrication, a small number of voices have offered arguments in favor of its authenticity. However, these are generally viewed with skepticism by mainstream historians and linguists.

Cultural Parallels with Biblical Narratives

Some researchers and faith-based groups have pointed out that the Walam Olum contains striking thematic parallels with the biblical account in Genesis. These include:

- A single divine Creator who forms the world.

- A serpent figure introducing evil and corruption.

- A great flood that resets humanity.

- Migrations and genealogies that resemble post-Babel dispersion.

Supporters argue that these similarities suggest a shared ancestral memory across cultures, and that the Lenape oral tradition may have preserved echoes of ancient events also recorded in Scripture.

Migration and Genetic Evidence

Some defenders of the Walam Olum point to genetic studies that confirm Native American migration from Asia across the Bering Strait. They argue that the migration narratives in the text align with this scientific understanding, lending credibility to the idea that the Lenape preserved a long oral history of their origins.

Historical Acceptance

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Walam Olum was accepted by many scholars as a genuine Native American document. It was used to support theories about the origins of Indigenous peoples and their connections to ancient civilizations. While later research cast doubt on its authenticity, the fact that it was taken seriously for so long is sometimes cited as evidence that it deserves reconsideration.

Rafinesque’s Linguistic Skill

Constantine Rafinesque, who published the Walam Olum, was fluent in many languages and had a deep interest in Native American culture. Some argue that his linguistic ability and dedication suggest he may have genuinely attempted to preserve a real tradition, even if imperfectly.

That said, these arguments are not widely accepted in academic circles. The strongest counterpoints include the lack of provenance, inconsistencies in the Lenape language, and the absence of corroborating evidence from Lenape elders or other tribal records. Still, for those interested in comparative mythology or the intersection of faith and anthropology, the Walam Olum remains a fascinating and provocative artifact.

OBJECTION DUE TO BIAS?

Some argue that skepticism toward the Walam Olum may be influenced not only by academic scrutiny but also by what its authenticity would imply, particularly in religious and cultural contexts.

Implications for Biblical History

If the Walam Olum were authentic, it would suggest that the Lenape people preserved a creation narrative, a serpent figure of evil, a flood story, and post-flood migrations that closely parallel the Genesis account. For some, this alignment is seen as evidence of a shared ancestral memory, a kind of universal testimony to the biblical story. That would challenge the notion that Scripture is isolated to the Hebrew tradition and instead affirm that its core truths echo across cultures and continents.

This idea is embraced by some faith-based researchers who see the Walam Olum as a bridge between Native American oral tradition and biblical revelation. They argue that dismissing it outright may reflect discomfort with the possibility that Indigenous peoples carried fragments of divine truth long before contact with Christianity. In this view, rejecting the Walam Olum could be seen as a way to protect academic or theological boundaries that resist integrating non-Western sources into the biblical narrative.

Resistance to Cross-Cultural Validation

There’s also a broader concern among some scholars and believers that mainstream academia tends to marginalize religious interpretations of history. If the Walam Olum were accepted as authentic, it could lend weight to the idea that the Bible’s events, such as the creation, fall, flood, and dispersion, are not just theological but historical, and that they left a global imprint. That would challenge secular frameworks that treat such stories as myth rather than memory.

In this light, some argue that the rejection of the Walam Olum is not purely about linguistic or archaeological flaws, but about what its acceptance would mean: a validation of biblical history through Indigenous testimony. That’s a provocative idea, and one that invites deeper reflection on how we weigh evidence, especially when it intersects with faith.

A Cautionary Note

Of course, it’s important to acknowledge that skepticism toward the Walam Olum is also rooted in legitimate concerns—like the lack of provenance, inconsistencies in the Lenape language, and the absence of corroboration from tribal elders. But this question opens the door to a deeper conversation: not just about whether the text is real, but about what we’re willing to accept as truth, and why.

FOR ADDIONAL READING AND STUDY

here are the articles I used to put all this together. I warn you… there are LOTS of rabbit holes to get lost in!

Scholarly and Historical Perspectives

Faith-Based and Comparative Views